Everyone who‘s had a discussion about Bitcoin or follows mainstream media‘s performance in the field knows that it triggers pretty extreme reactions. Plain rejection is the standard case, but there‘s also sarcasm, ridicule or sheer hatred of Bitcoin. The level of contempt is unparalleled and cannot be explained rationally. That‘s because there is no rationality involved. Rather, Bitcoin seems to embody a primal human fear of innovation. Where that comes from and how humanity has dealt with it over the past 2000 years is the subject of this article.

Of all the topics on which artificial intelligence can be consulted, Bitcoin is one of the most revealing. Even though there are obvious gaps in knowledge, AI often answers more soundly and positively than we’ve seen, for instance, in the press. That’s partly because AI lacks a few human traits: Fear, for example. It is not afraid of change and does not react in panic when the new (Bitcoin) world appears on the horizon. In humans, however, this trait, fear of innovation, takes control.

In Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the protagonist Bolkonsky notes that very intelligent people, even those known to be able to solve the most complex problems, can rarely accept simple and obvious truths if it would force them to admit false assumptions “which they have woven, thread by thread, into the fabrics of their lives.” That’s why discussions about Bitcoin are often impossibly. They don‘t find a common ground, no underlying assumptions or axioms that make rational arguments possible. This creates parallel worlds of argumentation that are impossible to reconcile.

“Men, including those at ease with problems of the greatest complexity, can seldom accept even the simplest and most obvious truth if it be such as would oblige them to admit the falsity of conclusions which they have delighted in explaining to colleagues, which they have proudly taught to others, and which they have woven, thread by thread, into the fabric of their lives.”

Leo Tolstoy (War and Peace)

The disparity of opinion is gigantic. Think about how Bitcoiners view the impact of their innovation as opposed to most critics: To them, Bitcoin is free and sound money with the potential to lower our time preference and positively change our society forever. The other group claims Bitcoin is simply a worthless air token that exists only to make early “investors” rich. It‘s their image of a perfect Ponzi scheme. Here, a firm belief in the separation of state and money that points our civilization toward a just and sustainable future. There, a fascination with the speculative object Bitcoin, which as a “climate killer” circulates intrinsically worthless invisible coins with which no one pays except criminals. How can such a disconnect arise? And how can it be resolved?

Bitcoiners often want to eliminate the contradiction through education and convert critics. Their solution is the orange pill, which comes with lots of education in the form of literature. And every now and then, with very open minds, it works. The underlying understanding of Bitcoiners is based on the fact that only a lack of knowledge leads to false assumptions and criticism. But that’s not all. If you follow the assumption, every remaining skeptic would only have to read one book to get on the right track and stack Satoshis tomorrow – it’s not that simple. The “orange pill” is huge. After all, Bitcoin stands for everything that is new. And it is a widespread myth that people are open to innovation. On the contrary, as history shows us.

The old world and the new

Bitcoin is not difficult to understand in its basic features. What makes it difficult to absorb, however, is the fact that Bitcoin pretty much overturns and challenges everything you’ve learned throughout your life. As many Bitcoiners preach, the system ultimately leads to the question, “what is money?” Bitcoin is practically the definition of radical innovation. So much so that it can hardly be described with appropriate words that we‘ve learned before 2009. It is primarily skeumorphisms, i.e., terminology from the familiar world that create a linguistic bridge from the old to the new. Sadly, no term actually describes what is really happening: The “coin” or “sending” of Bitcoin suggest a physical and spatial component, just like the “wallet.” But Bitcoin doesn’t exist in any place. “Mining” provides a nice image, but it is equally misleading because it does not explain that there’s no transaction without a miner. Hardly anything is labeled correctly because our words are too old.

Bitcoin creates its own institutions

For the life-experienced person, these are already major obstacles. But the innovation Bitcoin goes far beyond linguistic and technical components. Bitcoin creates new institutions and basically ignores all that a 20th century person grew up with. What are national borders, laws, banks or tax offices in a system that reinvents everything to do with money, decentralizing and dematerializing it in the process? No matter how much one pleads that the code and thus the technology behind Bitcoin are neutral. The idea is beyond revolutionary – and therefore highly suspect to most people.

Bitcoin is everything that was actually impossible in the old world: an electronic commodity without an issuer? A guaranteed yet digital scarcity? Money as a peer-to-peer network? A global currency that does not come from any country? A currency that hardly seems to be acknowledged as a unit of account? A fixed limited money that is nevertheless almost infinitely divisible? A pre-programmed monetary policy that no one can influence? The lack of understanding is pre-programmed in the truest sense of the word.

The innovation narrative

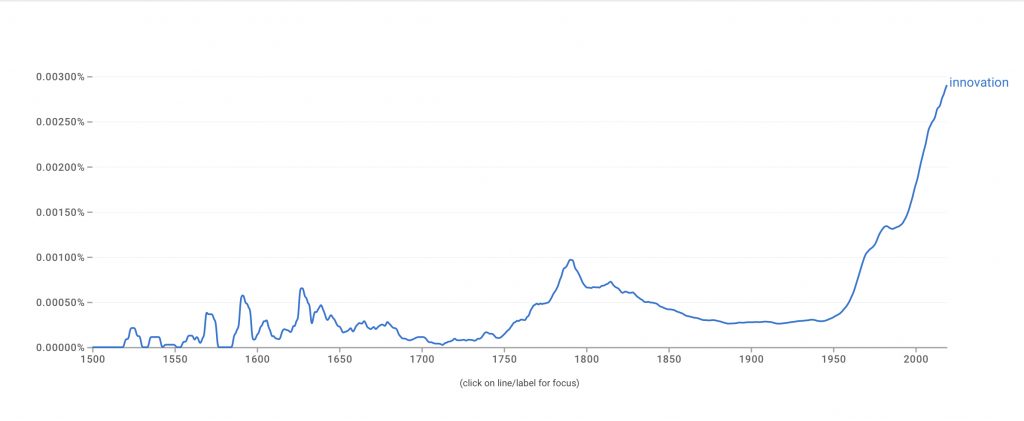

Bitcoin, and especially its rejection, shows us that it is a myth that we humans are just longing for disruption and change, patiently waiting for the meteorite of innovation. Rather, we long for the old and the tried and true – for firm traditions. Innovation is rather a narrative that advanced to a veritable hype in the 20th century that continues to this day. But experience shows that people almost always resist change and innovation. And in some cases, they do so for years and decades. Hardly any major invention has been able to gain widespread acceptance in just a few years. It is almost proof of a great innovation that it takes a long time to catch on. Bitcoin will take decades.

Blockchain not bitcoin?

Because of the anti-innovation mindset, the story of innovation is also, and above all, one of perseverance and persistence. It is a struggle against rejection and rejection. It is telling, for example, that much of the general public has ignored Bitcoin’s core innovation over the past decade: instead, buzzwords like “blockchain” have been cherry-picked and declared hype. The actual innovation of the Bitcoin system, which is all of its components working together, has been left behind and mangled; instead, a fragment is being used to „optimize“ supply chains and other logistical processes based on a questionable logic. There is a reason for this censure: “Blockchain” fits into the old world, in which companies and countries exist and users but also admins exist. The fact that politicians prefer to move in the wake of centrally controlled cryptocurrencies instead of relying on Bitcoin also speaks volumes.

People definitely seek change when it comes in small steps that improve their current circumstances. But innovations must always be administered in homeopathic doses so that there is no uncertainty. In fact, even most innovations that are thought to be major are hardly significant changes to already existing technology. The iPhone as a prime example of disruptive innovation did create a new market. But the elementary idea was based only on perfectly combining three objects that people had already used anyway. It was a disruptive innovation, but not a radical one.

Innovation in antiquity

And despite man’s basic conservatism, history is full of innovation. Aristotle writes in his Metaphysics that all humans “by nature strive for novelty.” It’s the essence of human nature. And so curiosity and rejection clash again and again. This was already the case in ancient Greece, where the concept of innovation found expression in the term “kainotomia“. From the very beginning, this had a political dimension, because it was about bringing “change to an established order“. Innovation, however, had a negative connotation and was fundamentally subversive and revolutionary in a negative sense.

Thus, for philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, innovation manifested itself in everyday subjects such as games and music. Athenians at the time saw various musical innovations that seemed to the audience to be a radical departure from tradition. Criticism and plenty of gloating hailed the new music, which Plato would have liked to ban completely. His argument against it was that innovation should never be more than a new combination of familiar elements and structures. For innovation to succeed, Plato argued, existing notions of value must be taken into account. Innovation in a vacuum would only lead to rejection and lack of understanding. Bitcoin is probably the best example of this.

But even though the existence of the Greek term suggests relevance, innovation was hardly an issue in the everyday life of the Greeks. In fact, it was barely used by ancient scribes. In contrast, the Romans had no term for innovation at all, even though there were many words for novelty, such as “novitas” or “res nova.” And similar to the Greek “kainotomia”, the verb “novare” had a negative meaning. The Romans had an interesting attitude toward novelty. For on the one hand, of course, they were great inventors, producing amazing technical achievements and engineering feats at all levels. On the other hand, they certainly drew boundaries when innovation became too revolutionary.

Tiberius and the flexible glass

For example, a story is passed down about Emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD), to whom a Roman glazier wanted to demonstrate a groundbreaking glass. Its special feature: it did not break. Pliny reports that his invention was called “vitrum flexile,” meaning flexible glass. The craftsman presented the emperor with a beautiful transparent vase, which he dropped on the floor. Although it should have broken into 1000 pieces, it remained intact. According to the story, Tiberius was visibly impressed, but quickly asked the glazier whether he had told anyone about his invention of unbreakable glass. The answer: no one. Tiberius then had the man killed and his workshop destroyed. His fear was very likely that the new material would sooner or later reduce the value of the imperial gold or silver.

The story is interesting in view of the fact that the Romans used many other inventions that were not far from flexible glass, and also made material more durable and better. For example, the Romans had developed a special composition of concrete. By adding small lumps of lime to the material, they caused the “opus caementium” to have a “self-healing” effect. When liquid entered, the calcium was released from the lumps and filled the gaps. The concrete was highly innovative. But long-lasting concrete was not subversive. Flexible glass had crossed the boundary of innovation. Analogous to our time: blockchain is fine, but Bitcoin goes too far.

Revolution, heresy and individualism

We often forget in the hype of renewal that innovation has historically almost always been seen as a vice, sometimes explicitly forbidden by law. The term was repeatedly used deliberately as a linguistic weapon by opponents of change, especially until the 17th century. People were literally accused of having “innovated.” The focus was primarily on the subversive and revolutionary level of meaning. For a long time, the innovator was considered a heretic and was called such – by clerics, monarchists, and conservatives in general. Innovation, revolt, or heresy were practically synonyms.

“It is hardly possible to make any innovation (…) without using new words and phrases, or giving a different meaning to those that are received; a liberty which, even when necessary, creates prejudice and misconstruction, and which must wait the sanction of time to authorize it.”

Thomas Reid, An Inquiry into the Human Mind (1764)

Of course, people still invented and innovated, but the anti-innovation mindset meant that it took a long time for new things to finally catch on. The Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid said at the end of the 18th century that innovation was an action that led to prejudice and misinterpretation even when it was necessary. An innovation “must wait the sanction of time to authorize it.” Innovation is closely related to individualism. For the one who innovates takes the freedom to contribute something of himself. He does not submit to the established order and tradition. Innovation is an individual construct, so to speak.

Bitcoin ignores tradition

Public opinion on Bitcoin can also be viewed from this angle. Because even if Bitcoin has a long history, which is mainly characterized by the preliminary work of many cypherpunks, the “P2P Electronic Cash System” ignores all institutions and traditions of our current society in an unprecedented way. Bitcoin is not issued by states and the money supply cannot be controlled by politicians or central bankers. Bitcoin is not reported anywhere and has no de facto regional origin. The legitimacy of a transaction is not determined by human institutions such as courts or banks, but by a history shared on all nodes.

In principle, Bitcoin has its own jurisdiction. And even its own chronology. The production of money ignores national borders, states and laws. In short, Bitcoin ignores every existing and established institution traditionally responsible for money, topped by the fact that it was obviously the idea of a single person, or at least a small group of people – flawlessy heretic.

The innovator: from heretic to creative genius

As we know, the concept of innovation took a turn in the 20th century. With the end of World War 2, the phenomenon for the first time acquired a positive connotation, most often associated with the work of Josef Schumpeter, because he associated innovation with technological progress and productivity. After the second world war innovation was now no longer subversive, but simply – and in a positive sense – non-traditional. Thus, the innovator was not a heretic, but perhaps a nonconformist deviant. Sometimes this even made him a creative and a genius. He is the one who brings change, who among other things increases productivity.

“After the second world war innovation was no longer subversive, but simply non-traditional. Thus, the innovator was not a heretic, but perhaps a nonconformist deviant. Sometimes this even made him a creative and a genius.”

Henceforth, however, the term was used so broadly and frequently that it wore thin. Author Clive Staples Lewis warned as early as 1960 that it was degenerating into a “semantic zero” that ended up having no meaning in terms of content. We see the result today. Everything is innovative and everyone is a disruptive innovator. The term is now no longer an indictment, but even becomes a self-description. There are innovative gadgets, apps, websites, and of course innovative companies, offices or even governments. And interestingly, most of them instinctively oppose real innovation when it happens.

Every institution is anti-innovative

In fact, true innovation is almost an impossibility for any established institution. This is because any company that wants to strengthen and establish itself and its position thinks statically. So does a state that thinks within its own boundaries. All established institutions have grown slowly and want to remain as they are. They are anti-innovative by their very existence. So are politicians who would like to ignore Bitcoin because by adopting it they would be challenging their own foundation.

But ignoring isn’t everything. The reactions to Bitcoin are symptomatic of the fact that the general attitude toward innovation has changed only gradually and on the surface. The scope for individuals to change in our society is certainly greater than it used to be. But whenever something crosses the boundaries of tradition, skepticism and contempt spread. The accusation of heresy reemerges instantaneously.

Innovation was revolution and heresy, but was also associated with disease, seduction, or downfall. This is exactly the spectrum in which Bitcoin moves in the media every day. Never ignored or forgotten, Bitcoin is covered in gloating, antagonized, and its raison d’être doubted. Although Bitcoin has existed for over 14 years, its imminent demise is predicted. The topic is so appealing that some authors have downright specialized in Bitcoin’s demise. And no argument, no metric, no matter how scientifically raised, and not even massive price increases are able to appease the critics who have already formed their opinions.

Bitcoin is nonconformism

We associate heresy with religion, with people who were burned in the Inquisition. The origin, however, is secular. In ancient times, the Greek hairetikós referred to a state in which one could “choose.” It thus had an individualistic undertone. Even as late as the 14th century, “heretic” had the meaning of not conforming to an established doctrine or tradition, in addition to being religious. Bitcoin is obviously the most extreme form of nonconformism.

“Bitcoin is well on its way to becoming a tradition itself. And the most effective tool for adoption is not a gigantic “orange pill,” but the innovator par excellence: time.”

Francis Bacon described innovations insightfully in “Novum Organum” (1620): “Innovations … at first are ill-shapen. They are like strangers … what is settled by custom is fit … whereas new things piece not so well. They trouble by their inconformity.”

But even as Bitcoin ignores tradition and alienates conservatives, adoption is inevitable. Because with each passing day, Bitcoin is well on its way to becoming a tradition itself. And the most effective tool for adoption is not a gigantic “orange pill,” but the innovator par excellence: time.