Objectively speaking, Bitcoin is already a massive success. In just 12 years, Satoshi Nakamoto’s idea has grown from being a conceptual PDF file in 2008 to storing around 1 trillion USD in 2021. This and any number from other metrics are testament to a form of mass adoption that only compares to the phenomenon of the internet in its early years. Still, despite this track record, the negative news and dystopian scenarios continue. “Bitcoin obituaries” are still very much alive. But instead of deploring said negative news, we should celebrate them. Why? Because they’ve been a completely normal side-effect for paradigm-shifting technologies ever since the printing press. Below is an overview of the patterns that, all throughout history, have signaled nothing less than: Change is already here.

Bad Bitcoin news has grey hair

There’s an obvious dilemma when it comes to interpreting history and Elon Musk nailed it with his famous saying “in retrospect, it was inevitable,” after buying Bitcoin worth 1.5 billion USD for Tesla. This is an acknowledgment of the fact that we have a hard time connecting the dots moving forward and need the rear-view mirror to judge something properly. Few people realize when a chapter ends and a new one begins. And the attitude towards change also depends on our age. As author Douglas Adams noted, “We find things developed before we turn 35 exciting and good. But we treat most innovations that come after 35 with growing skepticism.” This age division clearly works brilliantly: Bad news about Bitcoin has grey hair.

1995: “Resisting Virtual Life”

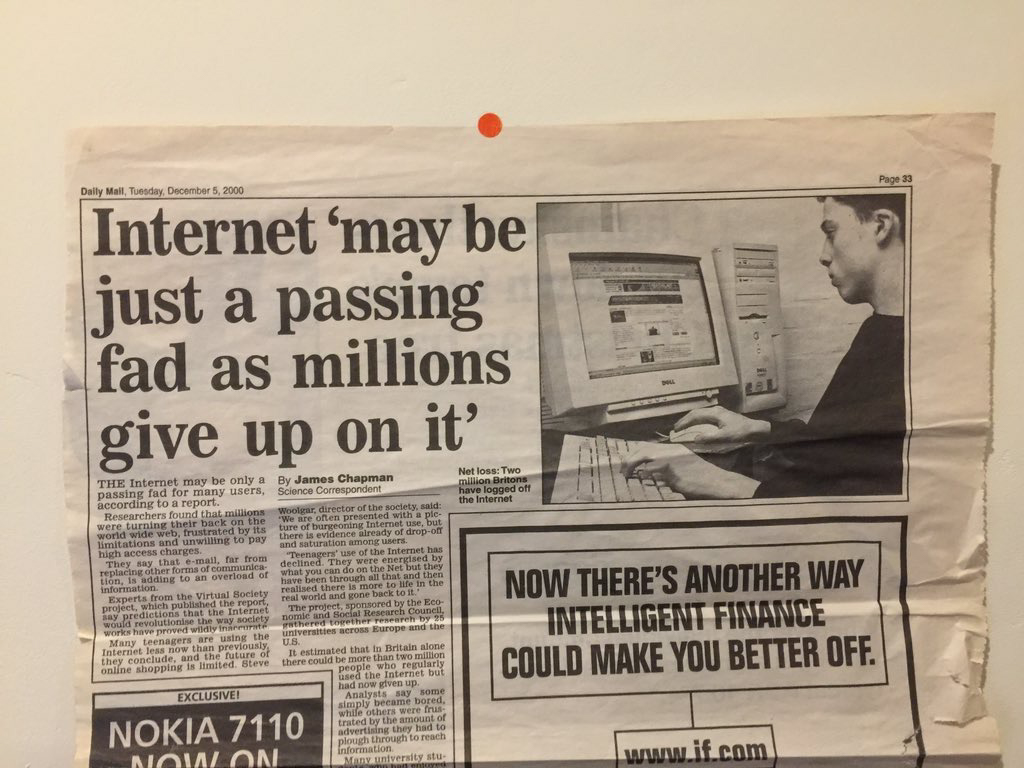

The negative news spiral rhymes with the 1990s and the rise of the internet. In the adolescent days of online, not everyone saw its big potential. And keep in mind that it was far more difficult to connect to the internet than it is to use Bitcoin today. Up until 1993, the use of the internet for commercial purposes was forbidden according to the “acceptable use policy.” But even after the introduction of the Netscape browser and growing commercial use, mainstream media didn’t embrace the technology: In 1995, journalist Clifford Stoll wrote for Newsweek, reflecting on the question of whether the internet will make governments more democratic: “Baloney. Do our computer pundits lack all common sense? The truth is no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.” He was not alone. The same year saw the publication of “Resisting the Virtual Life,” an anthology whose only intention was to prove that the internet sucked and would bring nothing but economic instability, oppression, suffering and erosion of values.

“Do our computer pundits lack all common sense? The truth is no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.”

Clifford Stoll (1995)

Even the much-celebrated Robert Metcalfe joined the crowd and famously said in 1995: “I predict the Internet will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.” Even two years later, Paul Krugman compared the economic impact of the internet to the fax machine. Besides arguments about how it wouldn’t work, there were also health concerns for the “always-on” generation. Published in 2005, a CNN article argued that email was hurting the IQ more than smoking pot. Despite all the criticism, of course, the internet kept on growing, as did the number of users. In 1997, there were 16 million Internet users worldwide, and this number reached over 5 billion in 2020.

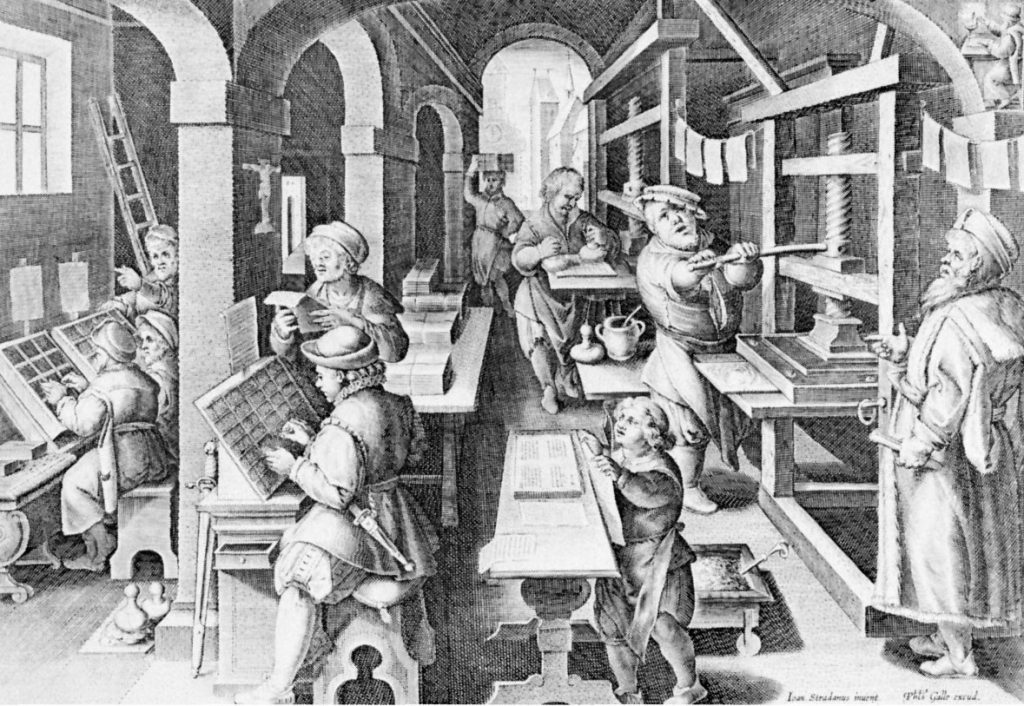

15th century printing – an exponential growing industry

While the impact of the Internet is often compared to that of the printing press, let’s take a quick look at the reception of the latter in the 15th century. Just like Bitcoin today, Gutenberg’s invention brought many advantages: The accessibility and portability of the pocketbooks helped the spread of literacy; The printing press could create a much bigger number of copies at a faster rate; The copies were more accurate and contained fewer errors; Plus, printing could reach more people over a wider area. In short, the printing press made it possible to collect and organize knowledge, as well as pass it on perfectly— which is why it grew so quickly. Just 30 years after the first Gutenberg Bible, the Netherlands already had printing shops in 21 cities, while Italy and Germany had shops in more than 40 towns each. By 1500, more than 1000 printing pressure were operating in Western Europe, producing 8 million books.

“… the confusing and harmful abundance of books.”

Conrad Gessner (1545)

At the same time, printing attracted the same negative news as Bitcoin today or the Internet in the 90s, even with similar arguments. For instance, Swiss biologist Conrad Gessner disapproved of printing for fear it would lead to a massive information overload. He even urged monarchs to limit and regulate the trade in order to prevent the poor public from suffering from the “confusing and harmful abundance of books.” Sound familiar? Similar arguments were also voiced when newspapers became ubiquitous. As nonsensical as it may sound, newspapers were said to isolate readers and further detract the news from the pulpit. Even health concerns were part of the choir: An article in the weekly medical journal The Sanitarian argued that schools exhaust children’s brains with too much information as a result of printing. They named “excessive study” as a cause of madness.

Even the “lack of intrinsic value” argument that seems to be married to Bitcoin news resembles some of the arguments brought forth against the printing of books: In the 16th century, abbot Johann Trithemius, a lexicographer, argued that printing shouldn’t replace the work of the monks. For one, because he liked monks, and secondly, because printed books were not of “real” value as their paper just wasn’t as “permanent” as the parchment used by the monks. This argument was further solidified by the belief that the mere act of printing a book meant that you didn’t understand your subject, which is reflected in his famous saying: “He who ceases from zeal for writing because of printing is no true lover of the Scriptures.”

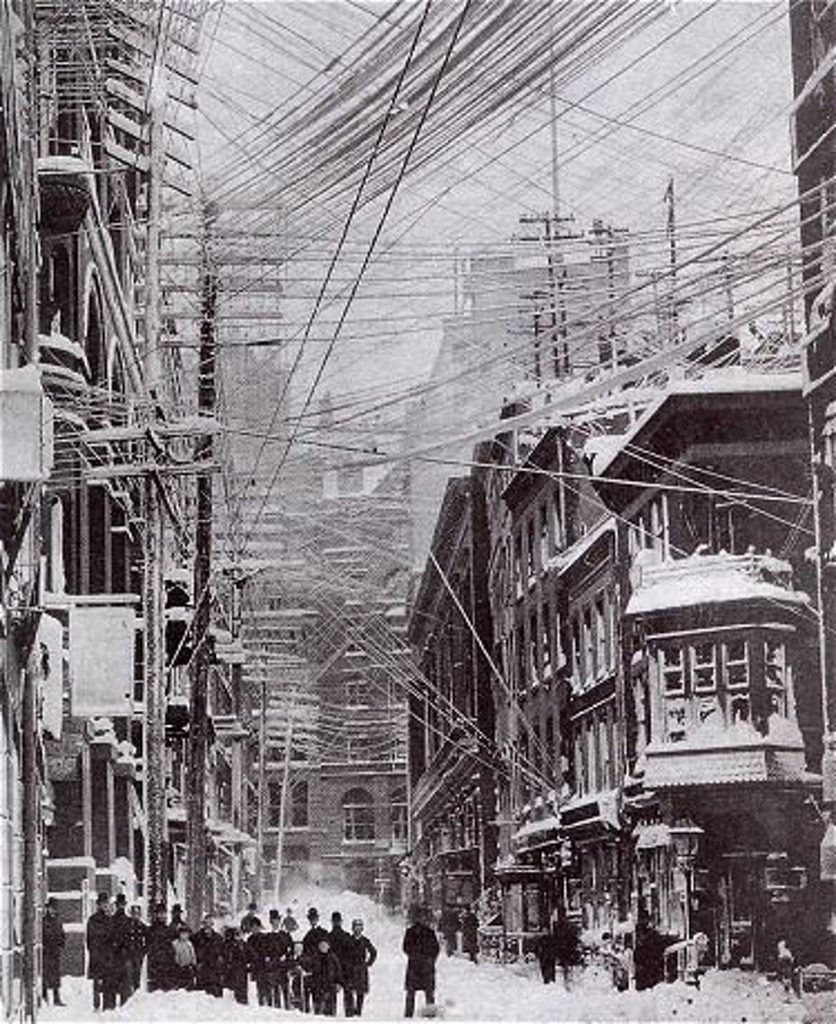

Addictive loudspeakers & electrocuting doorbells

Basically, the negative narratives accompanied every great technology of the modern age. The information overload theme was recycled time and again, even for the arrival of the radio. In 1936, a music magazine with the forward-thinking title “Gramophone” condemned the radio for instilling in children the habit of dividing their attention quickly between assignments and the addictive loudspeaker. When electricity came to light up our cities, many deemed it too dangerous. Apparently, even U.S. President Benjamin Harrison had White House staff turn the lights on and off for him because he was scared to get electrocuted. This fear of new technology even extended to electric doorbells. They took a long time to be accepted for similar reasons.

The Technophobia Movement

Alongside all the aforementioned patterns, there’s also pure technophobia based on a fear of disruption. In fact, this is at least an honest phenomenon — striking back at the thing that threatens your existence. It became a sort of movement in England at the dawn of the industrial revolution. With the development of new machines that were capable of doing the work of skilled craftsmen using unskilled, underpaid men, women, and children, those who worked a trade began to fear for their livelihoods. In 1675, a group of weavers destroyed machines that replaced their jobs. By 1727, the destruction had become so prevalent that it was declared a capital offense.

Therefore, negative news isn’t indicative of a failing technology. In fact, it’s almost like the opposite is true. More often than not, when the same arguments emerge repeatedly, with themes such as moral decline, information overload, or a threat to mental and physical health, chances are it’s the result of a state of shock. If you really want to understand the potential impact of a new piece of technology, try to understand instead what problems it proposes to solve and how fast it grows. If it grows like Bitcoin, don’t worry — it will change life as we know it.