Bitcoiners are among the few people who make a cult out of spending as little money as possible in our current consumer culture. With memes like “Stacking Sats,” “Hodl,” or “BTFD” (“buy the fucking dip”), they not only intelligently overcome the emotions of the market. But, there’s much more to it: It’s the rebirth of a savings culture. And wasn’t it actually extinct? To understand the phenomenon of saving and the peculiarity of Bitcoiners, let’s take a closer look at what’s going on.

Saving is an often-underestimated act, even if it sounds super dull – especially in German, phonetically at least. The one doing the saving is the “Sparer,” while Italy at least calls the person a “risparmiatori.” However, it’s anything but trivial to define saving. After all, the word’s original sense contains “preserving” and leaves many questions unanswered, such as what happens with the money afterward. Spent later, reinvested, or just hoarded?

Saving, however, is a fundamental economic activity that allows us to build up capital in the first place – one of the most important aspects of saving. This is the only way to achieve progress and prosperity. Ludwig von Mises called saving the “foundation of human civilization” and remarked that no immaterial goals could be achieved either without the accumulation of capital.

“saving and the resulting accumulation of capital goods are at the beginning of every attempt to improve the material conditions of man; they are the foundation of human civilization”

Ludwig von Mises (Human Action)

The sociologist Max Weber also saw the aspect of restraining oneself, as every person who saves does, as a cornerstone of human civilization. After all, unspent money does not disappear. Instead, especially in ascetic societies, it ends up being reinvested rather than consumed. In his work on the Protestant work ethics and the spirit of capitalism, he describes how the religiously influenced lifestyle indirectly gave rise to modern capitalism: Material success could be a sign of being chosen by God. Smart people then tried to do good business – but were not allowed to spend the money and had to reinvest it.

The religious lifestyle was above all: overcoming the “state of nature,” which consisted only of giving oneself over to emotional impulses. Protestant life, however, was a single exercise in self-control and deferred gratification. That is why the frugal life often has a positive connotation, not only in Protestantism.

“One gives freely, yet gains even more; another withholds what is right, only to become poor.”

Proverbs 11:24

However, frugality has also been highly controversial for centuries. Even in the Bible (Proverbs 11:24), there’s a reference: “One gives freely, yet gains even more; another withholds what is right, only to become poor.” And while frugality and saving aren’t the same things, there’s a big overlap.

In the 18th century, author Bernard Mandeville wrote the bee fable that popularized the “paradox of saving”: using the example of a bee colony, he showed how, in his opinion, frugality and virtue led to the decline of the economy and culture.

With “The Grumbling Hive,” Mandeville inspired economists such as Adam Smith and the philosopher David Hume. Then, in 1920, the authors Foster and Catchings took up the thesis of the downward spiral of savings once again in “Business without Buyers.” They even set up a research community for it and offered a whole $5,000 to anyone who could disprove their thesis – but decided that no one among the 435 entries had successfully done so.

While F. A. Hayek dealt with it in a very nuanced way in his 1929 article “The ‘Paradox’ of Savings,” John Maynard Keynes tried to further substantiate the theory of “underconsumption” in “The General Theory” in 1936 and to show the Keynesian limits to the troublesome savings habit.

The only point on which all authors agree is that saving goes far beyond private budgeting in its effects. In combination with interest, it is an essential economic factor. After all, another can borrow against a fee that one person saves. In this interplay, interest aligns with productivity and consumption. Or as Alfred Lansburgh, aka “Argentarius” wrote: “It attracts commodity rights when it is high and repels them when it is low.”

Banks played a central role as far back as the High Middle Ages. They rewarded savers for their low-time preference with interest through the lending business. Deposits were significant for banks as a source of liquidity, even though fractional reserve holdings had a long tradition. It was not uncommon to issue more bills than money deposited – since not all savers wanted their money simultaneously. Which, however, did happen in crises.

“A penny saved is a penny earned.”

Benjamin Franklin (Poor Richard’s Almanack / 1737)

Although saving was questioned again and again economically, people did it at all times and in all cultures. This is evidenced by a wide variety of money boxes from all over the world in which people store their savings. As Max Weber explains above, people were saved in ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, China, and America. One of the most famous figures in popularizing the slightly secular version of the Puritan lifestyle was Benjamin Franklin. In Poor Richard’s Almanack in 1737, he famously wrote: “a penny saved is a penny earned.”

Many historical money jars were richly decorated and elaborately crafted, showing the ritual value ascribed to keeping them. The modern piggy bank also emerged from this tradition. The shape was based on the ancient clay pots being made of an orange clay called “pygg.” As an allusion to the similarity to the English word for pig, the first piggy banks emerged in the 19th century – English humor that we live to this day, at least in savings bank advertisements for children.

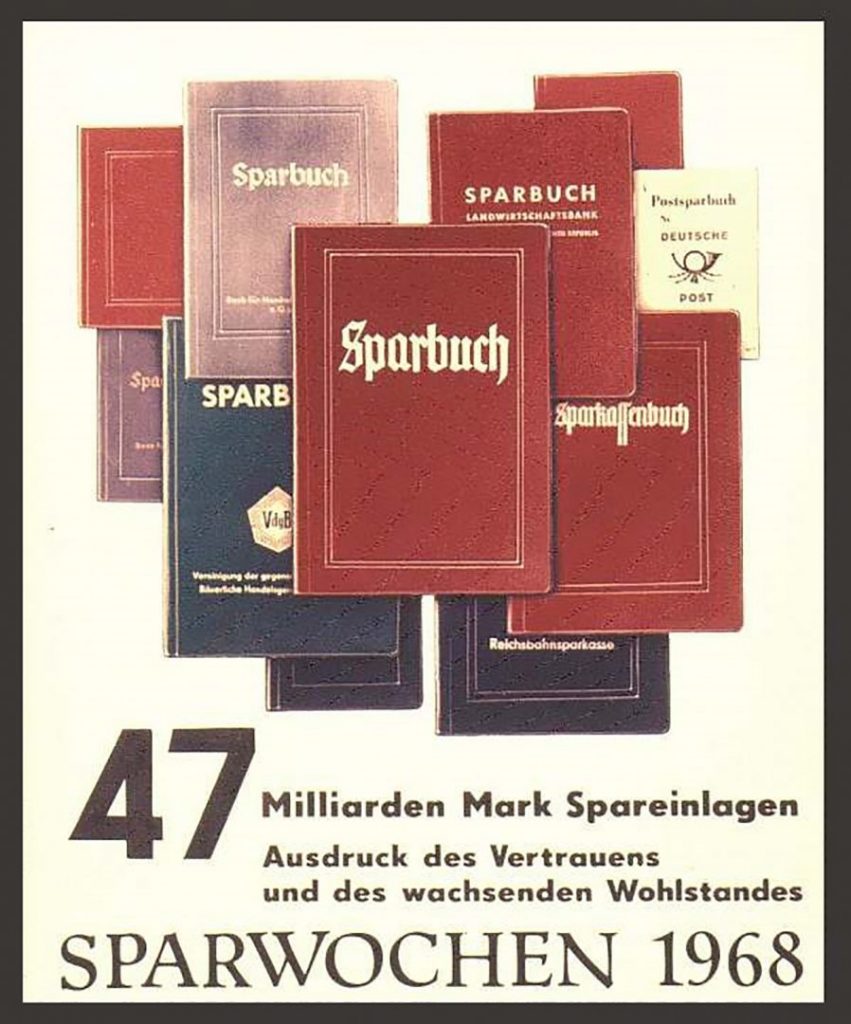

Saving beyond the clay pot and interacting with a bank presupposes trust in that institution. This was, however, put to the test at the beginning of the 20th century. However, it must be noted that despite the world wars, Weimar hyperinflation, or the banking crisis of 1931, it was quite possible to motivate the population to make savings deposits with banks. To reinforce this, World Savings Day was created in 1924 – a global advertising campaign for the savings account. More than 300 savings bank representatives from 28 countries attended the kickoff in Milan.

“Being thrifty is not primarily a national economic function, but a human attitude. […] Whoever saves wants to be free!

Theodor Heuss (Speech | World Savings Day 1952)

However, one observes how the seriousness slowly disappears in the course of the 70s and 80s. Children now increasingly came into play, whether due to rising inflation or the general zeitgeist. As a result, world Savings Day took on a solid pedagogical slant: well-off parents showed their happy children how to handle money.

World War II caused some interruptions, but savings continued to be promoted immediately after the war ended. Theodor Heuss’s speech on World Savings Day 1952 still shows the value attached to saving: “Being thrifty is not primarily a national economic function, but a human attitude. […] Whoever saves wants to be free! The same ethos can still be found many years later in the advertisements for World Savings Day.

The direction has hardly changed and remains without alternative in view of the barely existing interest rates. Wirtschaftswoche does not spare sarcasm in its article about the 2014 World Savings Day, which had become “a farce”:

“World Savings Day. That’s when Lisa and Hänschen go to the savings bank with their mom and deposit their savings in a children’s account. There are balloons, and the nice teller even has a little colorful piggy bank for the siblings. Tomorrow’s future customers have been recruited. At least that’s how savings banks and banks see the day in a past-heavy theory.”

But while the savings culture was being laid to rest, there was movement in the money story. In 2008, a new chapter in the history of money was opened quietly at first. Satoshi Nakamoto’s white paper was sent to the Cypherpunk Mailing List on October 31, 2008. Given the myriad references that lend symbolism to every number Nakamoto used in connection with Bitcoin – even his fictitious birth date – it should hardly be a coincidence that the white paper was released to the public not only on Reformation Day but also on World Savings Day 2008.

“It might make sense to get some, just in case it catches on,” Satoshi wrote in 2009. The price developments of the following years not only proved him right, but they also made every sale an outrageous act of far too much time preference. A pizza in 2010, an iPhone in 2012, or a car in 2013, every material item paled compared to the increase in value of Bitcoin. The opportunity cost alone of not owning Bitcoin made accumulating satoshis an imperative.

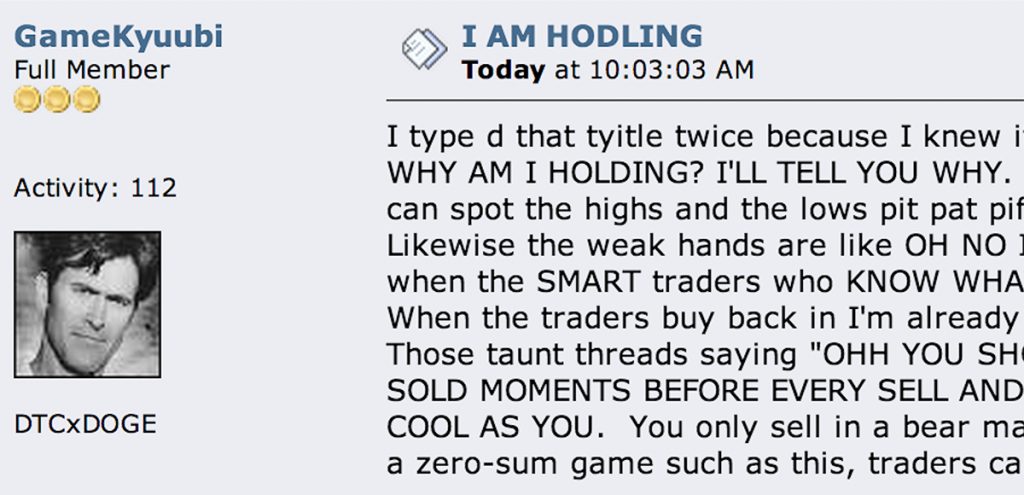

This realization gave rise to the memes that continue to shape Bitcoin culture today. In 2013, when user GameKyuubi wanted to share on the Bitcoin forum that he was holding on, he mistyped, “I am holding.” Born was #hodling, the preferred Bitcoiner strategy since time immemorial.

He who buys Bitcoin with full conviction does not think about selling. He doesn’t “invest,” as some belief. He saves in bitcoin. Similarly, user Uncle Marty first used the phrase “stacking sats” in 2017 – and again, referring to accumulation in the face of falling prices.

Since then, both stacking satoshis and frugal lifestyles have been part of Bitcoiners’ vernacular. Author and software developer Pierre Rochard suggested getting rid of anything non-essential to buy Bitcoin – sell your chairs. The site Bitcoin or Shit demonstrates how poorly any investment in material things would have fared against Bitcoin. As a result, Bitcoiners sell their too-expensive cars and other luxury items … to save money. But on what?

For Bitcoiners, saving has become almost a mystical end in itself. Knowing that the price could rise immeasurably, material things become insignificant in the here and now. Medium-term show-off items like the infamous “Lambo” have long since been written off and have made way for a utopia that hardly contains anything material. There are lots of castles, houses with gardens or happy family life. It’s much more of a utopian image of society, partly based on some of the golden eras of human history. Where will it go from here? Let’s watch.